Ellika Larsdotter was born on April 25, 1703 in Nysund, Sweden, a small farming community. Most of the details of her life have been lost to history, but it is likely she lived all of her life in Nysund. If she travelled at all, it would probably have been within Orebro, the county where Nysund is located, or Varmland, the rural county beside it. On September 8, 1721, when she was 18 years old, she married Mattes Eriksson, the son of another Nysund farmer. When they married, Ellika was eight months pregnant. As liberal as Sweden is now, three centuries ago their marriage would have been scandalous in a small farming community whose members belonged to the Church of Sweden, a Lutheran denomination.

Their child, Kirstin Mattsdotter, was born on November 8, 1721 and died at birth. Ellika lingered for ten days before dying herself on November 18. Her husband’s mourning period must have been brief because he married Ellika’s 27-year-old sister Catharina the following year. That marriage was more fortunate for both husband and wife, who lived for many years afterwards and produced seven children, the third of which was Erik Mattsson.

His birth is meaningful to me because Erik grew up to become one of my great-great-great-great grandfathers. I’m relating this story because had Ellika Larsdotter not died after giving birth to her child, Mattes Eriksson would not have married Ellika’s older sister, Catharina, and Erik Mattsson would not have been born, which means I would not have been born.

In the strange vicissitudes of life, I owe my existence to Ellika Larsdotter’s premature death.

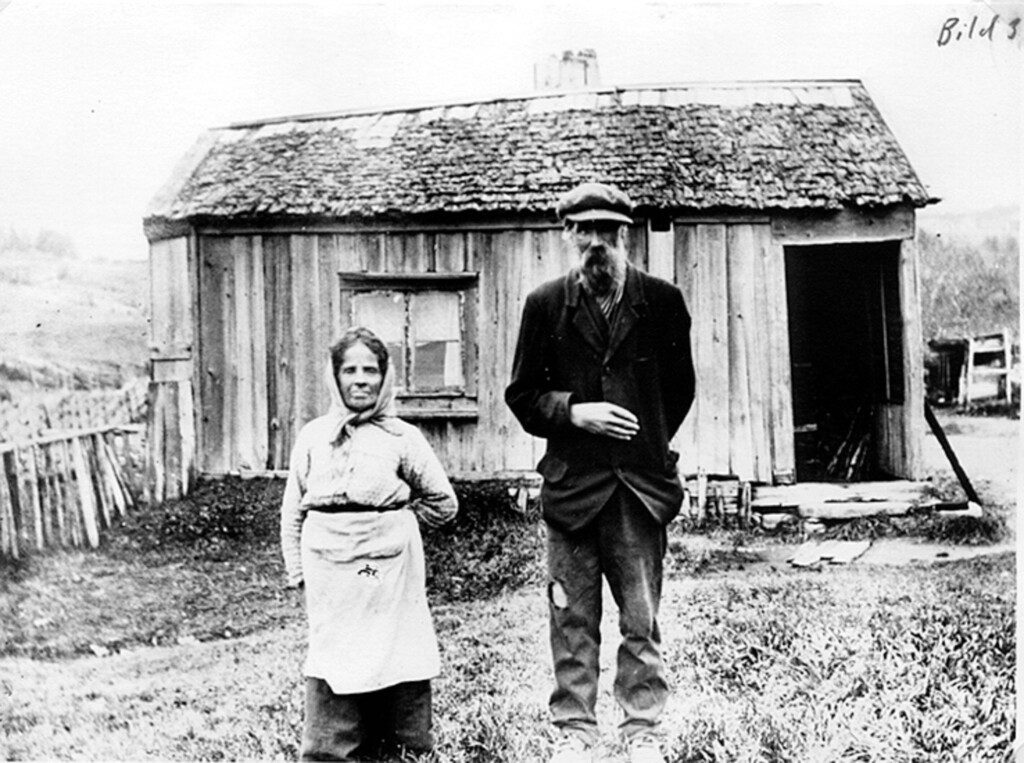

Since discovering Ellika’s story during geneology research, I’ve thought about her often, wondering what sort of person she was, what she dreamed of, what made her happy and sad. I hope her brief life was filled with joy, but life was tough for farmers in rural Sweden three centuries ago. I doubt she had much schooling, and she would have had to work hard on the farm to help her family. She may have looked upon her marriage and pregnancy as a blessing, the start of a new life with her own family, despite the disapprobations she and Mattes must have received from local church gossips. It may have been a difficult pregnancy, and childbirth must have been painful, and then to linger for ten days knowing your child has died and growing weaker yourself. It was an unfortunate end to Ellika Larsdotter’s short life.

But I would not be here had she not died prematurely. I have too much empathy for her to say that I’m thankful she died. Perhaps it’s best to say I’m grateful for my own life and for how providence created the conditions that allowed me to be born 226 years after Ellika died. And this is really the point of my reflections: her death is not the only circumstance that led to me being born. Throughout the eons, there have been thousands if not millions of events and situations that led, via an impossibly quirky path, to my father and mother conceiving me when they did.

My parents’ existence depended on their parents meeting when they did, being attracted to one another and deciding to marry. Their existence depended on none of their thousands of progenitors dying of a disease before passing on their genes, or being thrown by a horse, or dying in a war, or moving away before they could meet the person they would eventually marry. My parents’ existence depended on their parents coupling on just the right day, and the mothers being fertile on that day, and the fathers’ being virile at that moment, and on that particular sperm cell fertilizing the egg out of the millions of other sperm cells instead.

The fact that I am here now writing this article is a miracle because so many things could have been different. Had Ellika Larsdotter not died, I would not be here. Had Mattes not married Catharina I would not be here. And so on through the millennia with every one of my ancestors, stretching back beyond history. The odds that I would be born are astronomically small when you consider all the circumstances that had to be just so. Any deviation from the path that led to me would have caused me not to be born. Any deviation out of trillions of possible deviations going back through human history.

Statisticians have calculated that the odds of any of us being born are about 1:6.5 trillion. That’s one in 6,500,000,000,000. Those are worse odds than winning the Powerball or Mega-Millions lotteries. I’m thrilled to say that I beat those odds and am here to write about it. You beat those odds, too. Congratulations.

Photo credits: first photo of Swedish farmers: Image ID: 2BDB6Y Matteo Omied / Alamy Stock Photo; second photo of Swedish farmers: Image ID: D7M6EW Atomic / Alamy Stock Photo; graveyard: Image ID: CRG65E blickwinkel / Alamy Stock Photo